Andrew Hodgson from Classical Source reviews LMP Southbank performance

Sunday, March 31, 2019 Southbank Centre, London – Queen Elizabeth Hall

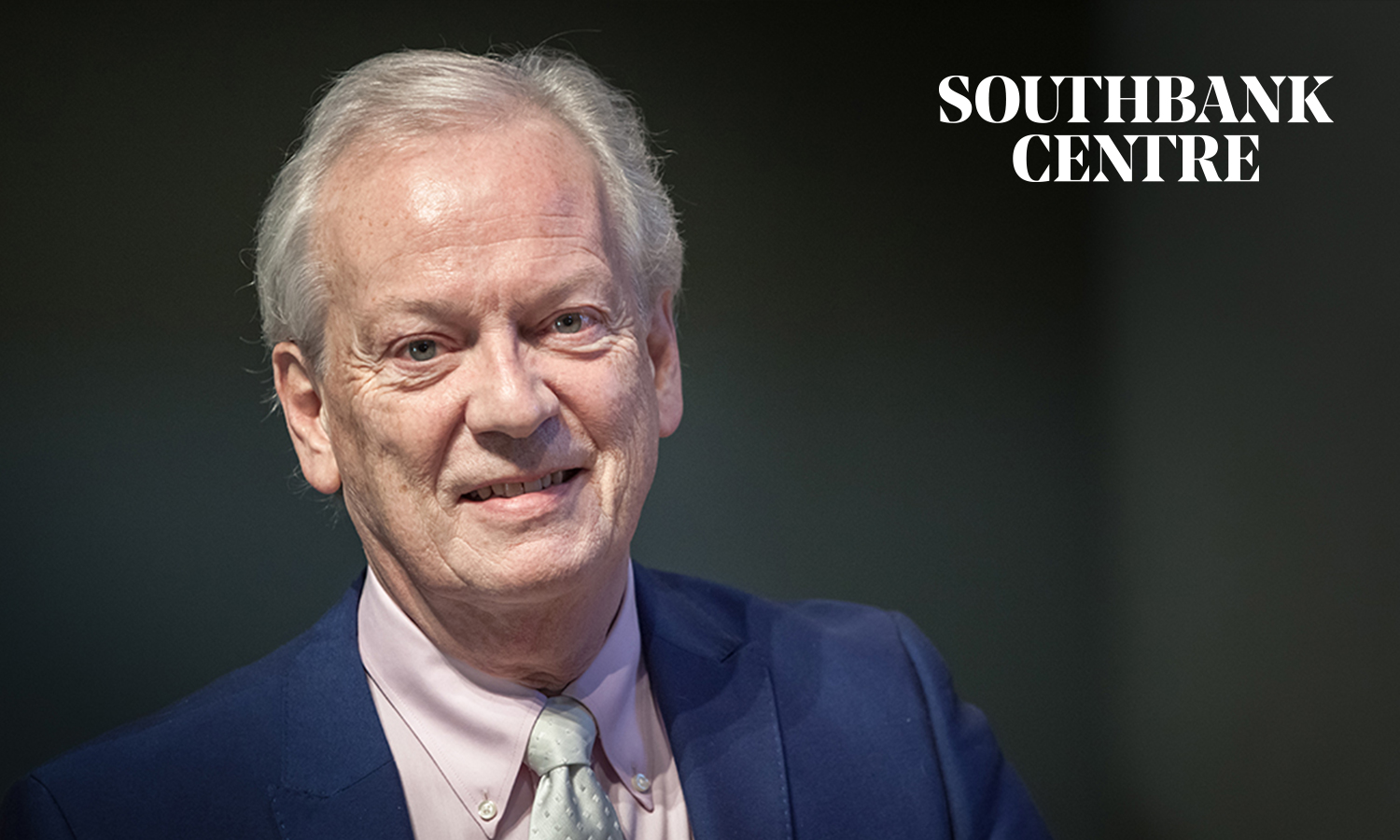

Haydn’s dramatic Symphony 95 – the only minor-key example among the twelve such works composed for London – suitably commenced this concert entitled “Celebrating Genius” given on the 287th-anniversary of the composer’s birth. Here was the best of a modern-instrument orchestra’s presentation of classical-period music. Supplemented by his two between-works talks succinctly describing the history and the nature of the music, Howard Shelley’s approach involved lucid balancing with notably clear definition of woodwind lines and sensitive phrasing which illuminated the melodies without imposing personal shaping upon them. Symphony 95 sounded large in scale as a result of the fully-blended sound.

Timpani, although played with hard sticks, was warmer and less incisive than expected and I wondered if the placing of them at the rear corner of the stage might have been the cause. Grandeur was the essence of the outer movements although the decision to use horns at the lower octave when in the key of C meant that richness rather than brilliance was the effect. The Trio section of the Minuet is a cello solo and Julia Desbruslais played it eloquently and with great sensitivity at an ideal tempo, a pity that the surrounding Minuet was taken faster than the Allegretto marking suggests. An assortment of between-movement clappers was present: their ill manners were particularly annoying when the conductor was about to bring down his baton to start the Finale and he was forced to wait until the noise stopped.

Shelley’s interpretation of Mozart’s A-major Piano Concerto was full of understanding and shapely current between piano and the London Mozart Players. It displayed the advantage of the soloist acting also as director. New to me were the technical devices used to facilitate this contemporary performance. When playing, to be properly visible Shelley sat at the keyboard with his back to the audience. A normal piano lid would have thrown the sound sideways so it was removed and replaced with a large oblong glass panel facing the audience meaning that through it Shelley and players could see each other. Now as conductor and director Shelley needed a score and this was represented by a tablet standing in front of him above the keyboard and as the end of each page was reached it switched magically to the next. So modern technology may seem surprising but the result was immaculate ensemble which enhanced a most-sensitive performance, comfortable in tempo and notable for fluency of pianistic passagework. The central Adagio typified Shelley’s skill moving calmly forward with gentle momentum within a slow chosen tempo and his approach to the Finale gave the appropriate sense of optimism.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Concertino (sometimes known as Piano Concerto No.1) is a delight. Written in 1799 when the composer was twenty-one it was originally for mandolin and orchestra but was revised for piano seventeen years later. It makes an excellent full-scale ‘concerto’ with a strong melodious Allegro moderato, a cheerful set of Variations on a child-like Theme and a Finale which, though melodically simple, expands joyfully. Alternations between piano and orchestra are not quite standard and sometimes the ideas are given fully by orchestra with piano as a sort of continuo. Shelley looked delighted to present this work and brought off the fearsome running passages effortlessly. A memorable performance and mercifully the clappers did not intervene.

Mozart’s ‘Haffner’ Symphony represents four of the six movements from a Serenade. In transferring from one to the other, Mozart added flutes and clarinets. The printed score lost the first-movement repeat marked in the original – this is unlikely to have been Mozart’s decision. Occasionally a conductor will revive the exposition repetition; Shelley did not do so but he added a spurious one to the Minuet. The reading was large in scale and it was a pleasure to hear such orchestral precision. Mozart’s intention that the Finale should be played as fast as possible was fully honoured and extreme swiftness was also the order of the day in the well-chosen encore – the ‘Frolicsome Finale’ from Britten’s Simple Symphony – real string virtuosity here.

Our Next Concert at QEH

Mozart, Beethoven, Hummel: Masters Loved and Lost

SUNDAY 9 JUNE, 3PM

MOZART Symphony No. 34 in C K.338

HUMMEL Piano Concerto in F

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 4 in Bb Op. 60

During their lifetimes, despite setbacks and hardship, Mozart, Beethoven and Hummel all enjoyed success. Mozart was acclaimed as the greatest of composers while Beethoven was proclaimed Mozart’s musical and spiritual successor. During his lifetime, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, a contemporary of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, also garnered praise and respect comparable to the masters. Yet today, while Mozart and Beethoven are still ‘box office’, Hummel is simply the support act.

In this special Sunday afternoon concert, the London Mozart Players and acclaimed pianist Howard Shelley, present all three composers with equal billing. Mozart’s ebullient and glorious Symphony No. 34 in C opens the concert, contrasting with the precision and muscular strength of Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony. Between the two symphonies, Hummel’s elegant Piano Concerto No. 6 in F sits comfortably, it’s unceasingly melodic and virtuoso piano writing clearly demonstrating why Hummel’s reputation should be reestablished in the classical repertoire.